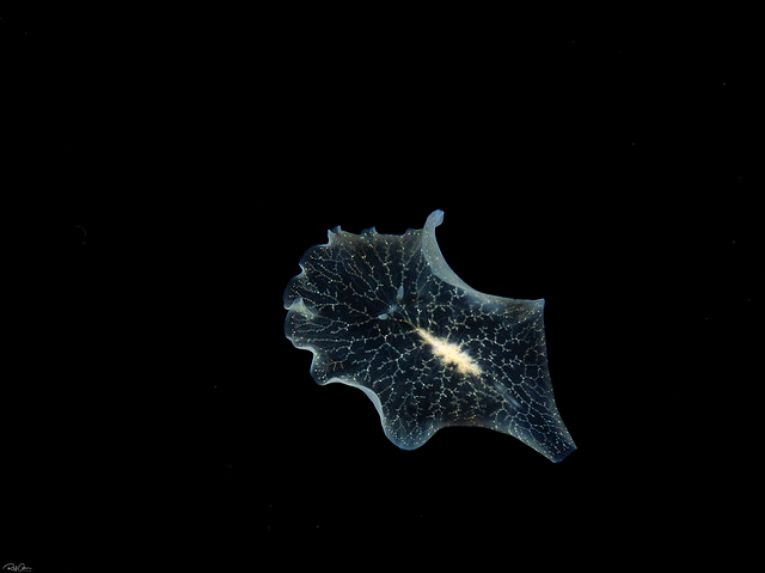

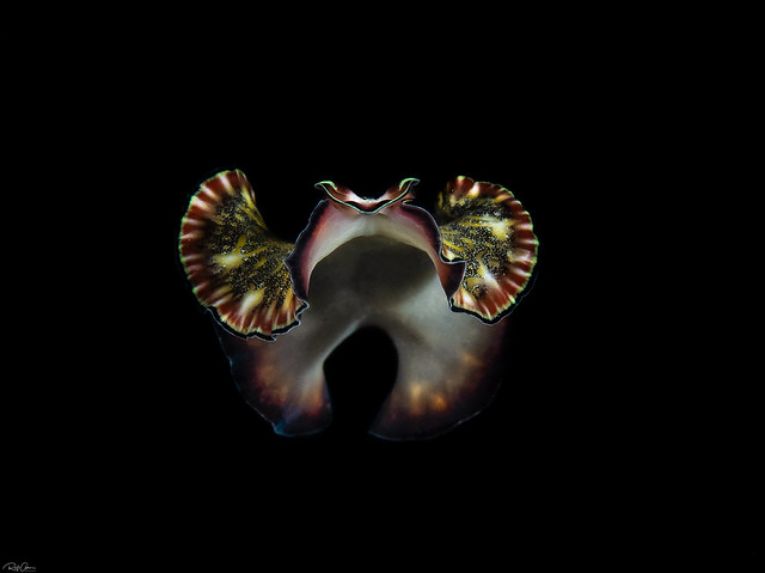

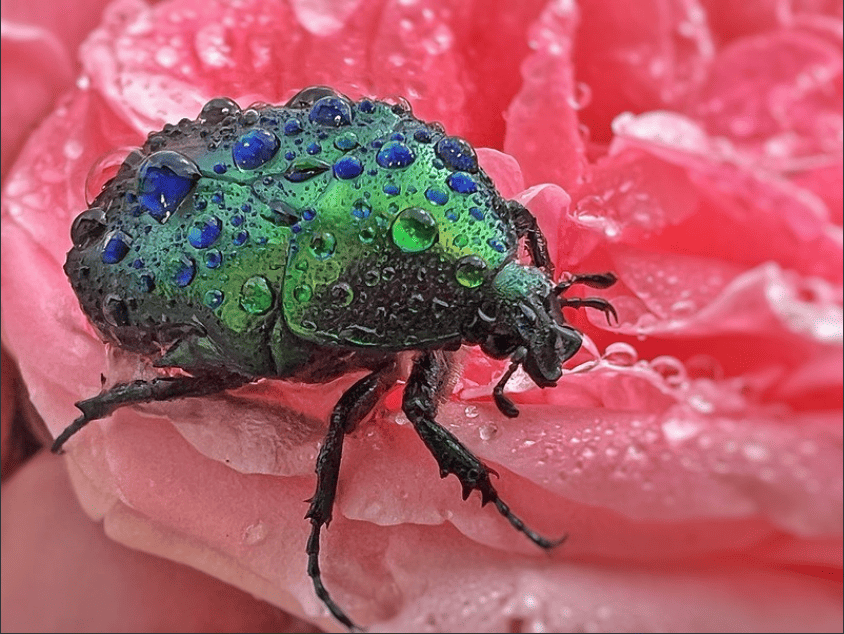

This creepy crawly was found living in a rarely used toilet in Brussels.

I was alarmed to find it. Is it a parasite? Hookworm, or roundworm?

Some history:

This is a rarely used part of the house. One day I discovered the toilet bowl was teeming with sewer drain fly larvae. Also creeped me out until I worked out what I was looking at. I’m not bothered about drain flies so I just left it alone. Returned to the toilet a couple months later and the trap was bone-dry. There was a hard blob of something.. mud, limescale, I don’t know. Not sure how it got there. It was the size of a golf ball so more mass than I would expect from limescale. I used a strong acid to descale the toilet. I made the toilet sparkling clean.

Then I used the trap to clean a dread-lock style mop because I could stuff it in there and squeeze out the the grime. And the mop could also reach deeper into the trap to clean the toilet better. Toilet water would become instantly black but easy to flush and repeat. After 10 or so iterations the water was still gray so I gave up.. maybe the mop should be bleached.. so I put the mop away. The mop was previously used to clean up cat urine (neighbors cat keeps entering my house, peeing on the livingroom floor and stairs, then bailing.. does not hang-out [why mark in a territory it does not intend to use?]). Anyway, I did not defecate in the toilet after cleaning it. Maybe urinated a couple times over the span of a couple months.

Then out of the pure blue I find this creepy crawly. Should I bring this thing to a doctor? I cannot work out how it got there or if it came from me. Perhaps equally important are the sand grains (50 or so?) around it.

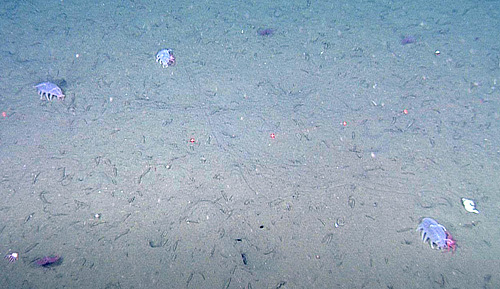

theory 1: it entered the cistern from the Brussels water supply, perhaps as an egg. Hatched in the cistern. Brussels water contains sand which builds up at the screens of the tap airators and also in the cistern. A typical flush does not bring any noticable sand into the toilet bowl, but maybe if a worm were in the cistern it would have moved the sand around so that a pinch of sand would go in a flush, along with the worm.

theory 2: it came in from the Brussels water supply and ended up in the sewer pipes like most of the water does, grew in the sewer pipes and crawled up into the toilet trap from the sewer side. As it crawled, sand and scum from the sewer pipe stuck to it and washed off it when it entered the trap.

theory 3: it came out of me and ended up in the sewer pipes and crawled into the toilet. No!!! I hope not. But if so, it’s the lower floor toilet that I use, so the worm would have to do a straight up vertical climb 1 story high inside of PVC. Seems unlikely.

theory 4: I leave the window open most of the time and the toilet seat up, so a bird could have flown in and dropped something in the toilet.

They all seem unlikely.