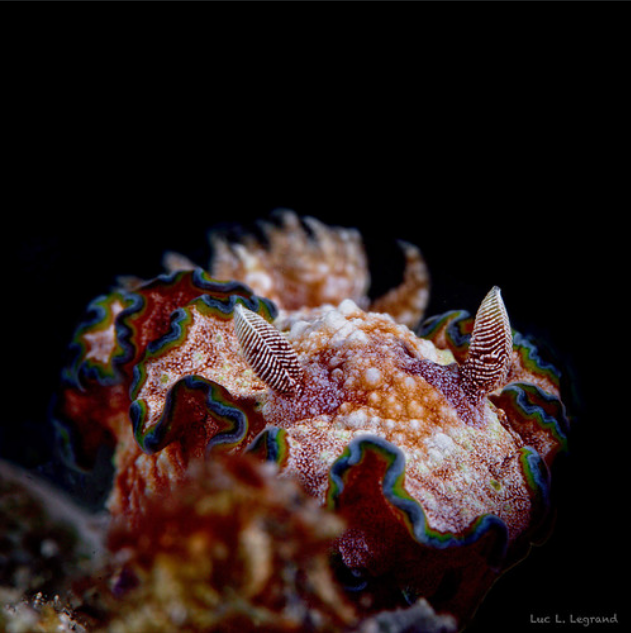

quinacridone

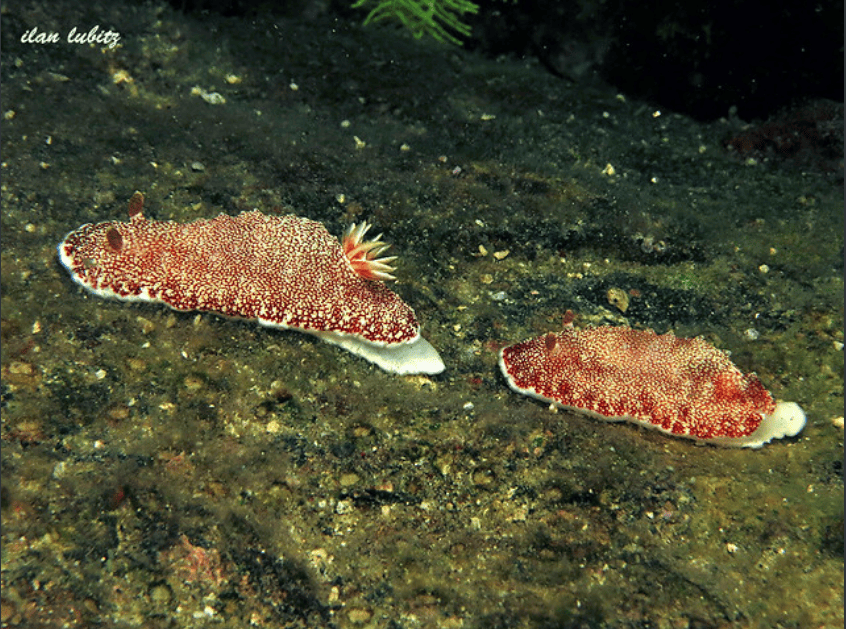

Main photo by ilan Lubitz

Elysia marginata are Sacoglassons (a type of sea slug) and are found in the Indo-Pacific ocean at depths of 0-10 metres

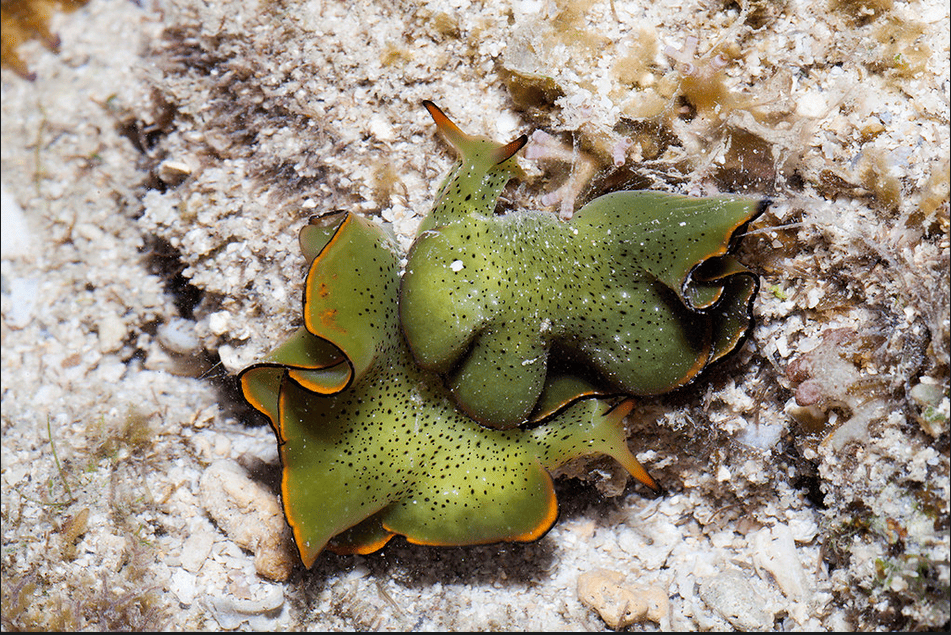

Above photo by budak

They eat algae and store the chloroplasts in its body. The chloroplasts continue to photosynthesize and provide its host with a source of food!

Above 'Pair of leaf slugs on algae. They feed on green algae and can grow from 3 to 8cm long. Photo by Wesley Oosthuizen.' source

They have the ability to regenerate a completely new body (including a new heart) from their head, after it detaches itself from its old body! (A process called autotomy- self amputation)

Above photo by Sonja Ooms

Their ability was discovered by Sayaka Mitoh, a doctoral student at Nara Women's University in Japan, who spotted the decapitated head of E. marginata circling its separated body in one of the tanks in the lab

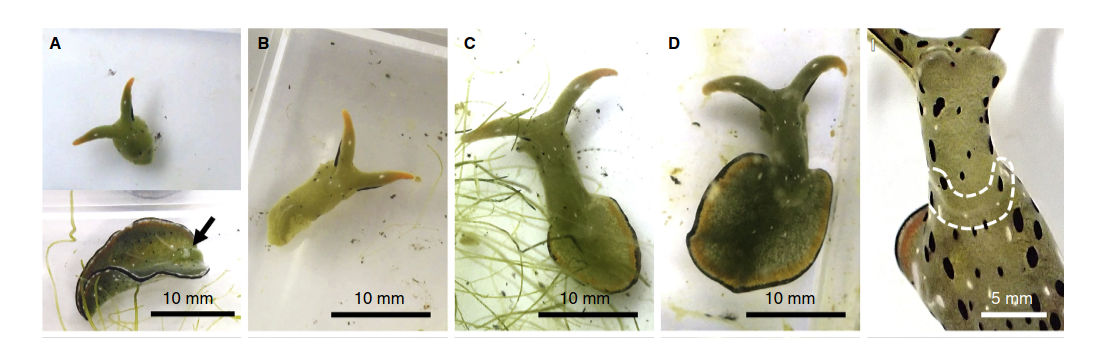

Above 'This image shows the head and the body of Elysia cf. marginata, a day after autotomy.' (Image credit: Sayaka Mitoh) source

Quite naturally she thought the slug would soon die, however..

"After a few days, the head started regenerating the body and I could see [the] beating of the heart. It was unbelievable," Mitoh told Live Science. "I was really happy and relieved when I found it could regenerate the body." source

- A, Head and body of Elysia cf. marginata, just after autotomy (day 0), with the pericardium (heart) remaining in body section (arrow)

- B, day 7

- C, day 14

- D, day 22, showing whole-body regeneration.

- E, Head and body of Elysia atroviridis (individual no. 1) just after autotomy (day 0).

Above text and photo source

The head continued to grow its new body over the next 3 weeks, including all vital organs, reaching about 80% of its original size!

Above gif source

"The [original] body continues to move and live for days to months," Mitoh said. "You can see the heart beating" inside them, she added. However, the decapitated bodies did not appear to be capable of growing new heads themselves. source

The old bodies remained active for several days to months, until they started to shrink, turn pale due to the chloroplast loss, and eventually died. The beating heart remained visible until the body had fully decomposed!

So, why such an extreme behaviour?

In other animals self amputation usually occurs when escaping a predator, however this may not be the case here....

Above photo by budak

The head can take several hours to detach from the body, so not exactly a quick get away from a predator

Instead it is suspected that it is a means of ridding itself of parasites. There is a slight groove towards the end of the head which acts as a breakage plane, and the similar head severing species Elysia atroviridis all had internal parasites when they detached from their bodies....

However, no parasites were detected in Elysia marginata that did the same.....

Above photo by Javier Diaz Frogmen

The ingested chloroplasts are thought to help in the regeneration of the new body and keep the head alive in the absence of the digestive system organs (which remain with the body).

One individual that was studied underwent autonomy and regeneration twice, which researches think is the limit...(which probably means it didn't survive the third time scientists went to work with a scalpel)

Interestingly this behaviour was only exhibited by young Elysia marginata. When older animals were decapitated their heads survived up to 10 days, and didn't regenerate before dying

Above photo by Antonio Venturelli

All information from wikipedia, here, here, here, here, here and here

As always I'm not an expert, any errors let me know in the comments and I'll edit

And I shall leave you all with a reprise of my current favourite gif....

Main photo, Halgerda batangas by Gerhard Batz

Firstly, the vast majority of photos are taken at depth so it's probably a good idea to be able to scuba dive.....and also most nudibranchs tend to look like this without the use of special lighting set ups

Above, by McChuckerson

Above by Go Zilla

(Please note, I'm not criticizing or taking the piss out of these photos or the photographers, I just want to show how nudis look under normal lighting)

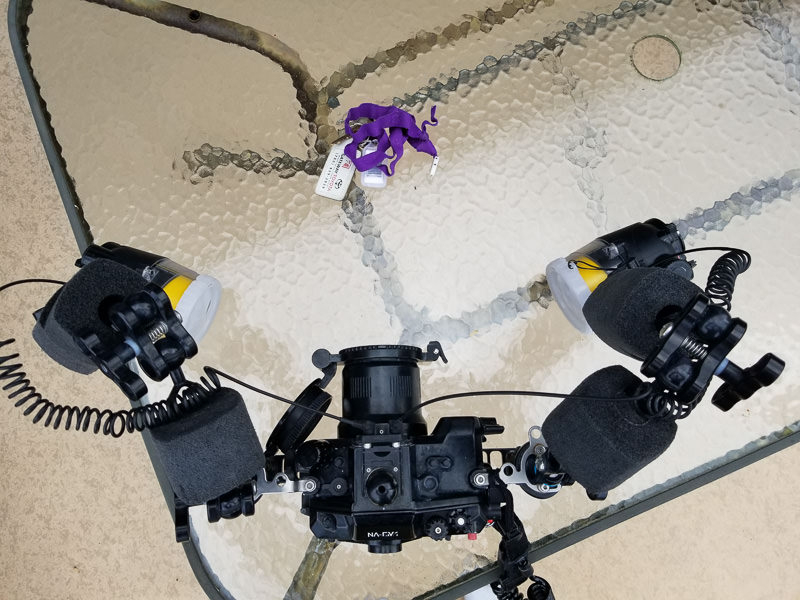

A lot of nudi photos have black backgrounds which are created by using a strobe lighting set up configured like this...

Above, 'This is how... (Bryan Chus) setup looks to get a successful test shot on land, using my 60mm macro lens (120 mm full frame equivalent).'

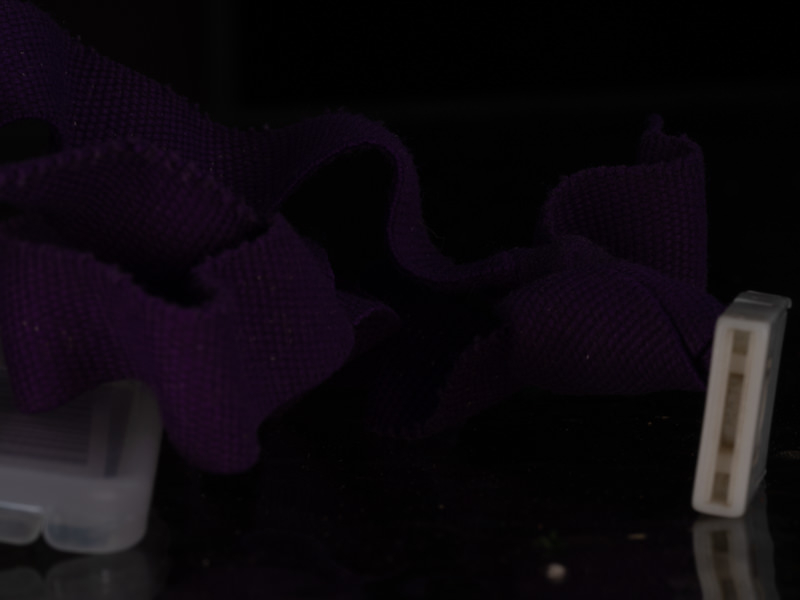

Above, 'Non-lit test subject using black background settings (1/320 sec, f/14, ISO 100).'

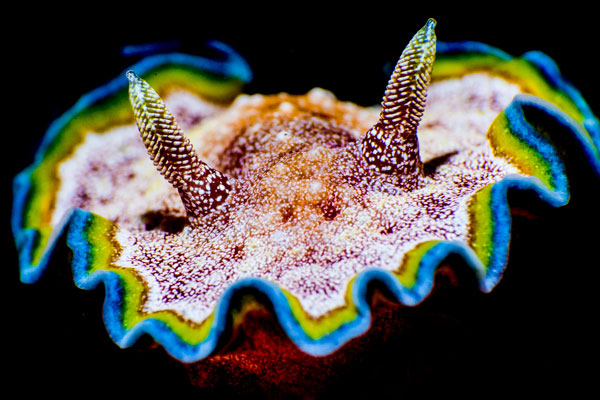

Above, 'Properly lit test subject with inward facing strobes.'

The photos give results like these...

Above, Janolus nudibranch

Above, 'Oxynoe jordani feeds on Caulerpa taxilfolia Canon 5DSr 100mm Lens ISO100 1/250 f/25' by Jenna Szerlag

Above by Andrey torchuck

Of course there's slightly more to getting an amazing photograph than just having the right set up....

Composition, highlighting natural features, symmetry, depth of field, background contrast, animal behaviour all play their role

Above, 'Showing nudibranch symmetry works well, like with this shot of a Nebrotha kuberyani. [Mike Bartick] particularly like[s] to shoot these guys because of their interesting facial features, texture and vibrant colors.'

Above, 'Chromodoris leopardis. Laying eggs is always a very interesting behavior to capture. The eggs are often brightly colored and textured. If eggs are found alone, inspect them, as other nudibranchs often feed on them.'

Above, 'Nembrotha chamberlaini. If there is an anomaly of some sorts that sets your subject apart for the norm be sure that this anomaly is the center of the viewers’ attention.'

Above, 'Extreme depth of field isn’t always necessary, but on a larger subject its hard to resist, especially when one is as colorful as this Hypseledoris. Backing away from your subject is an easy way to slightly increase your DOF when working with nudibranchs.'

Above, 'Using a quality diopter of +10 or greater will dramatically increase the size of very small subjects and allow you to fill the frame with very little cropping. These Castosiella kuroshimae are miniscule and nearly impossible to detect. Look on small algae on sandy dive sites.'

Above, 'Nembrotha lineota. Get low, get close and shoot up. Use negative space and be sure your subject's Rhinophores are sharp.'

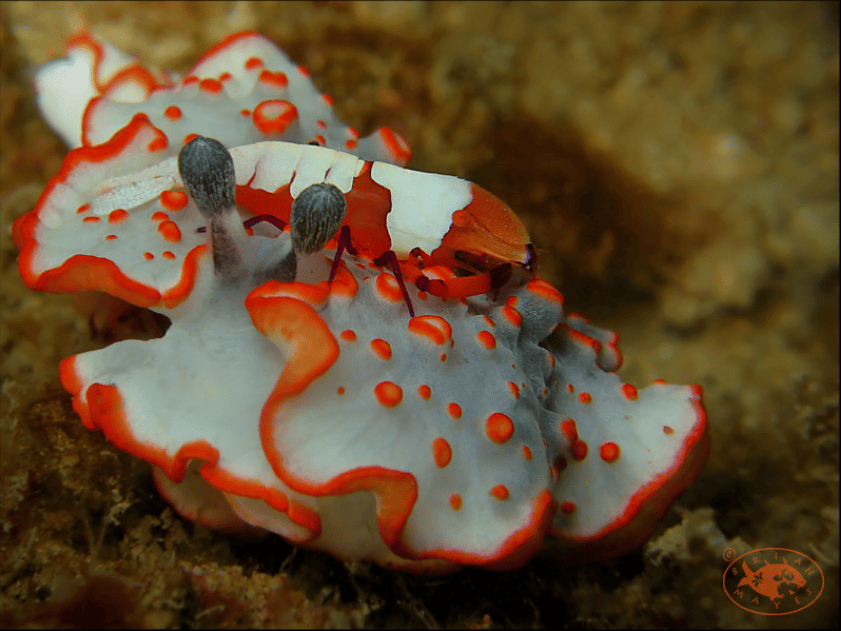

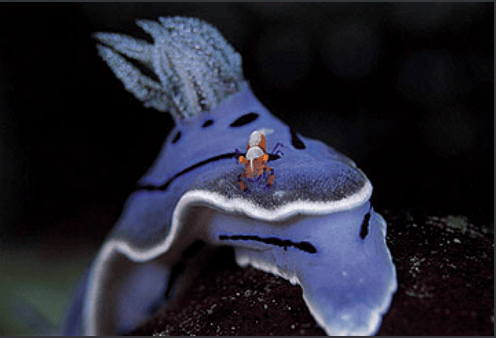

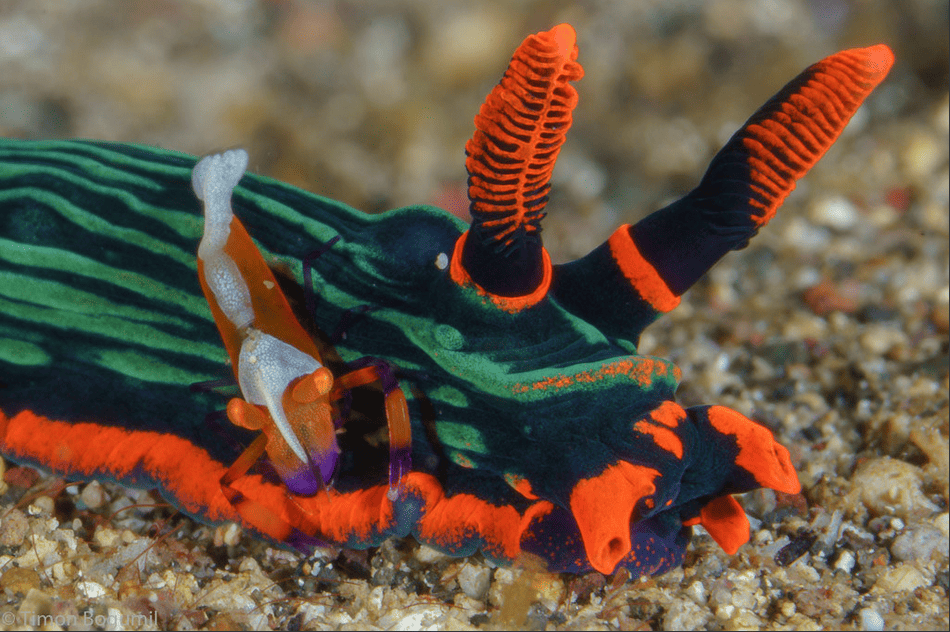

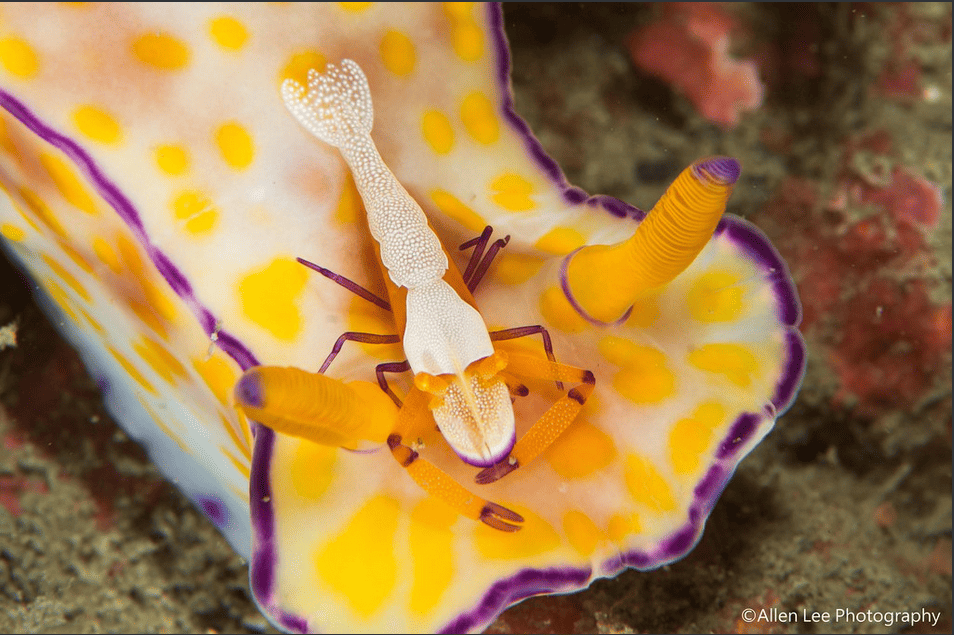

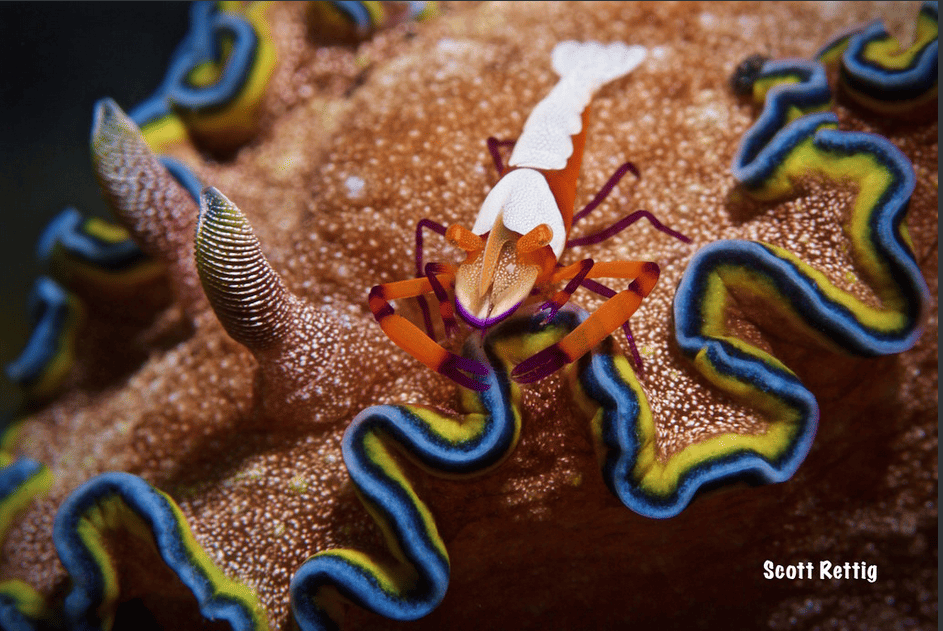

Above, 'Miamira tenue aka Ceratasoma tenue can grow to impressive sizes. Some are large enough to sport accessories like this emperor shrimp that lives a symbiotic lifestyle with its host. Keeping its hosts gills cleaned and rummaging for food as the nudi moves along the substrate is priority number 1 for the shrimp, and getting photos of them on the nudi are great behavioral images.'

Above, 'Mimicry is another behavior that an entire article could be written about, especially with these amazing Lobiger sp. Sap suckers live on algae that resembles green grapes. This image was shot in very shallow water in broad daylight. Using a high shutter speed will enable you to control the incoming light, even on the sunniest days. When a subject is tall, try turning your camera to the portrait position.'

Above, 'Glossodoris cincta. These larger nudis will fill your frame easily with or without a diopter. Paying close attention to the camber of your subject's Rhinophores will help with head-on composition. The gills of the cincta actually vibrate as they move and are fun to watch.'

Not all photographers use black backgrounds for their photos and the results are just as beautiful....

Above photo Thorunna australis, by elebe.foto

Above photo Hypselodoris bullockii laying eggs by Sonja Ooms

Above photo of Oxynoe olivacea by Jose Salmerón

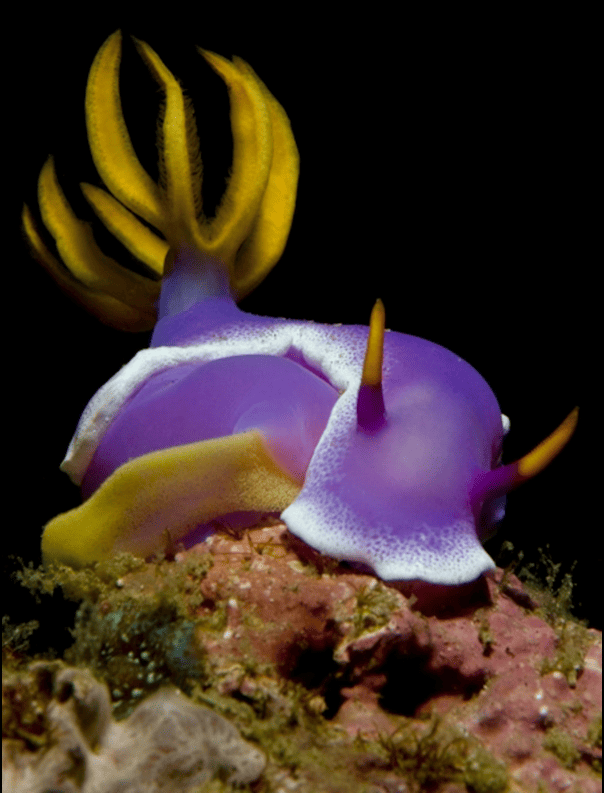

Beautiful photo that pops with contasting colours of Elysia marginata by elebe.foto

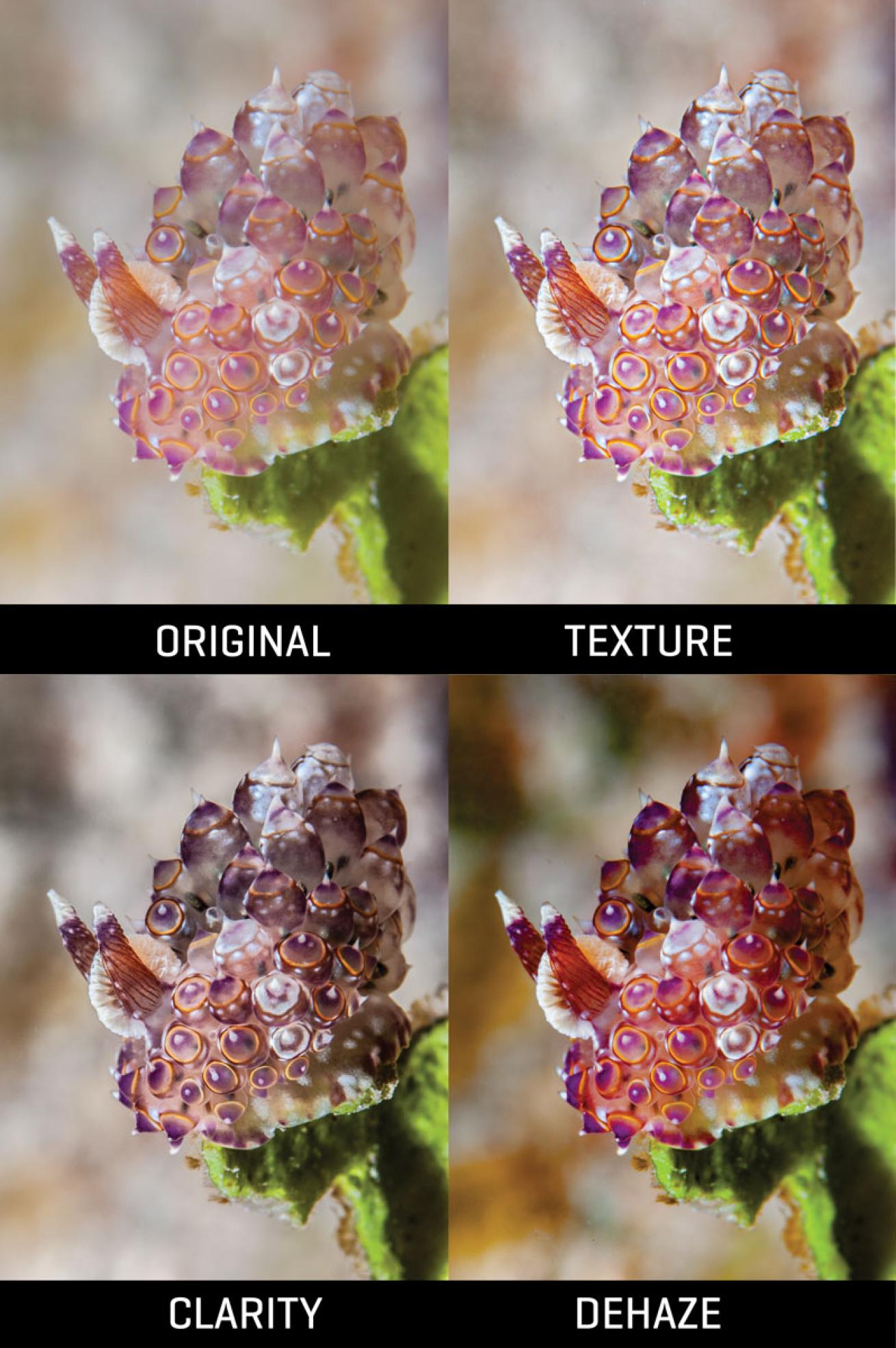

And also lets not forget the role of the computer in adding the final touches to a well composed and well lit photograph

Some photos may need a bit of work to either remove debris in the foreground or background that distract from the main focus point...

Others need work in making them pop more. Of course images can suffer through too much retouching, and also no amount of photoshop can save a poorly composed image....both sides of the debate are discussed here

Above, 'Here's how to make Texture, Clarity and Dehaze work for you.' photo by Erin Quigley

And finally a Super Pro photo by David Hall, below

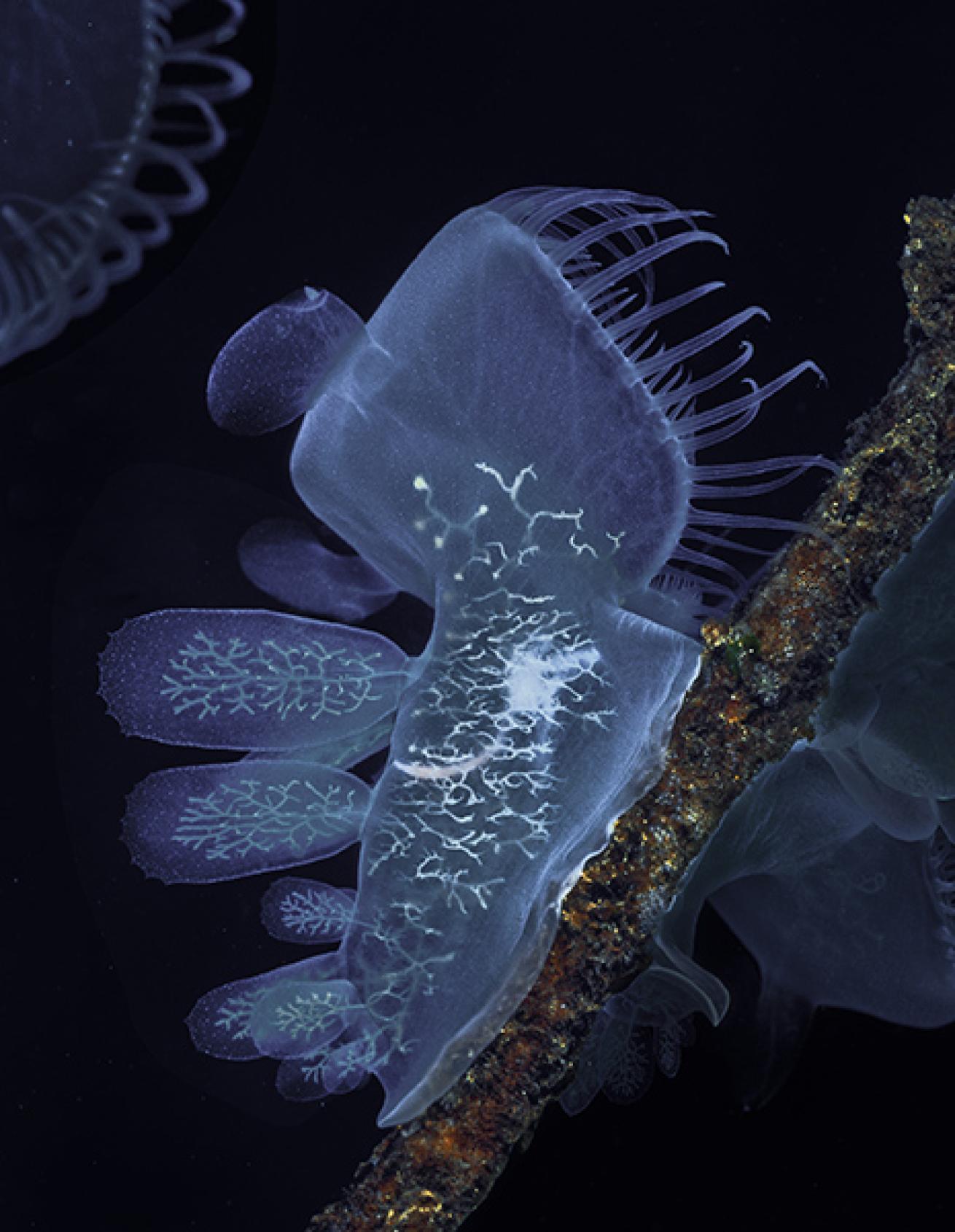

"Imagine a bull kelp forest in which the plants are completely covered with ghostlike animals expanding and contracting rhythmically,” photographer David Hall writes of shooting the hooded nudibranch, Melibe leonine, for his award-winning book Beneath Cold Seas: The Underwater Wilderness of the Pacific Northwest.

HOW HE GOT THE SHOT Hall used a Nikonos RS camera with a 50mm lens, two Ikelite SS-50 strobes and Fujichrome Velvia 50 film. Hooded nudibranchs are transparent, like jellyfish, and correct exposure can be difficult to estimate, so Hall bracketed the exposure generously. here

All information from here and here, unless otherwise stated

As always I'm not an expert, and certainly not one in underwater photography (I'm still trying to get to grips with terrestrial photography)

Main photo 'A giant dendronotid nudibranch swimming in mid-water'

Above, 'The opalescent nudibranch is a predatory mollusk with no shell'

Above, 'Hooded Nudibranchs on Kelp'

Above, 'Hooded Nudibranchs'

Above, 'Hooded Nudibranch, Melibe leonina - British Columbia, Canada'

Above, 'Opalescent nudibranchs and ascidians'

Above, 'Sea Lemon Nudibranch, Anisodoris nobilis - British Columbia, Canada'

Above, 'Nudibranchs (Nembrotha kubaryana) feeding on stalked ascidians. All nudibranchs are carnivorous, mostly preying upon sessile invertebrates such as ascidians, sponges, bryozoans and cnidarians (hydroids, corals, anemones). (Komodo, Indonesia) (photo: Gayle Jamison)'

Above, 'Nudibranch, Miamira magnifica - Izu, Japan'

Above, 'Hypselodoris infucata; Lembeh Strait, Indonesia'

Selected underwater photography here, more nudibranchs, and his books

Title photo by Doug Anderson

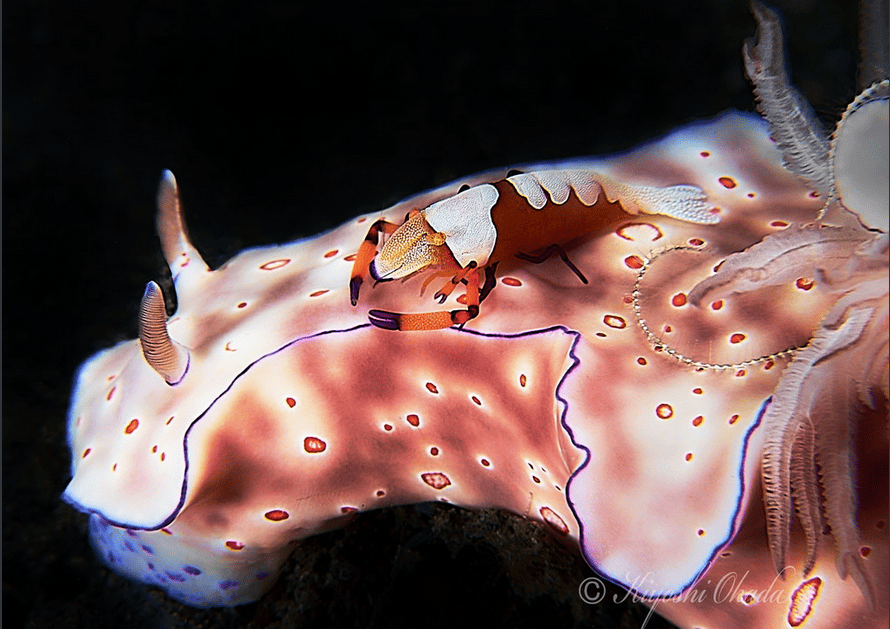

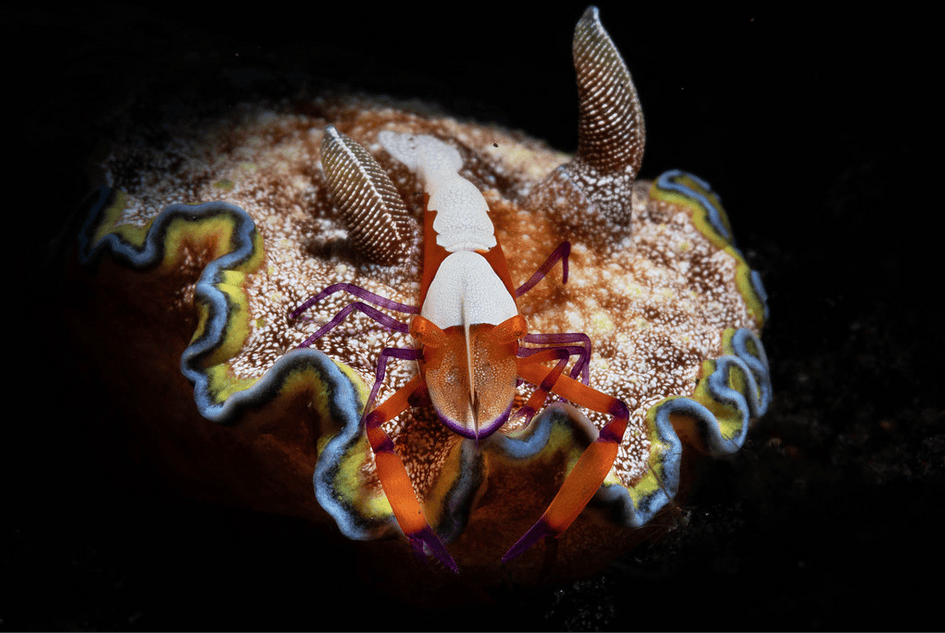

More photos of Emperor shrimp (Periclimenes imperator) riding on various nudibranch hosts...

Solo riding....

Above photo of Ceratosoma trilobatum, by Jack

.....or with a pal....

Above photo of Ceratosoma trilobatum, by Jack

...Tandem....

Above photo by Stefano Scortegagna

Above photo of Ceratosoma gracillimum with eggs by Pauline Walsh Jacobson

Above photo of Ceratosoma tenue by Eric Cheng

Above photo of Nembrotha lineolata, by Colin Salmon

Above photo by Doug Anderson

Above photo by Michel Duchayne

Above photo of Dendrodoris tuberculosa, by Brian Mayes

Above photo of ceratosoma nudibranch, by KIYOSHI OKADA

Above photo of Ceratosoma tenue, by Gomen S

Above photo by Colin Robson

.... Hail The Emperor!

Above photo of Hypselodoris infucata, by Anilao~Critters

Title photo by Todd Aki

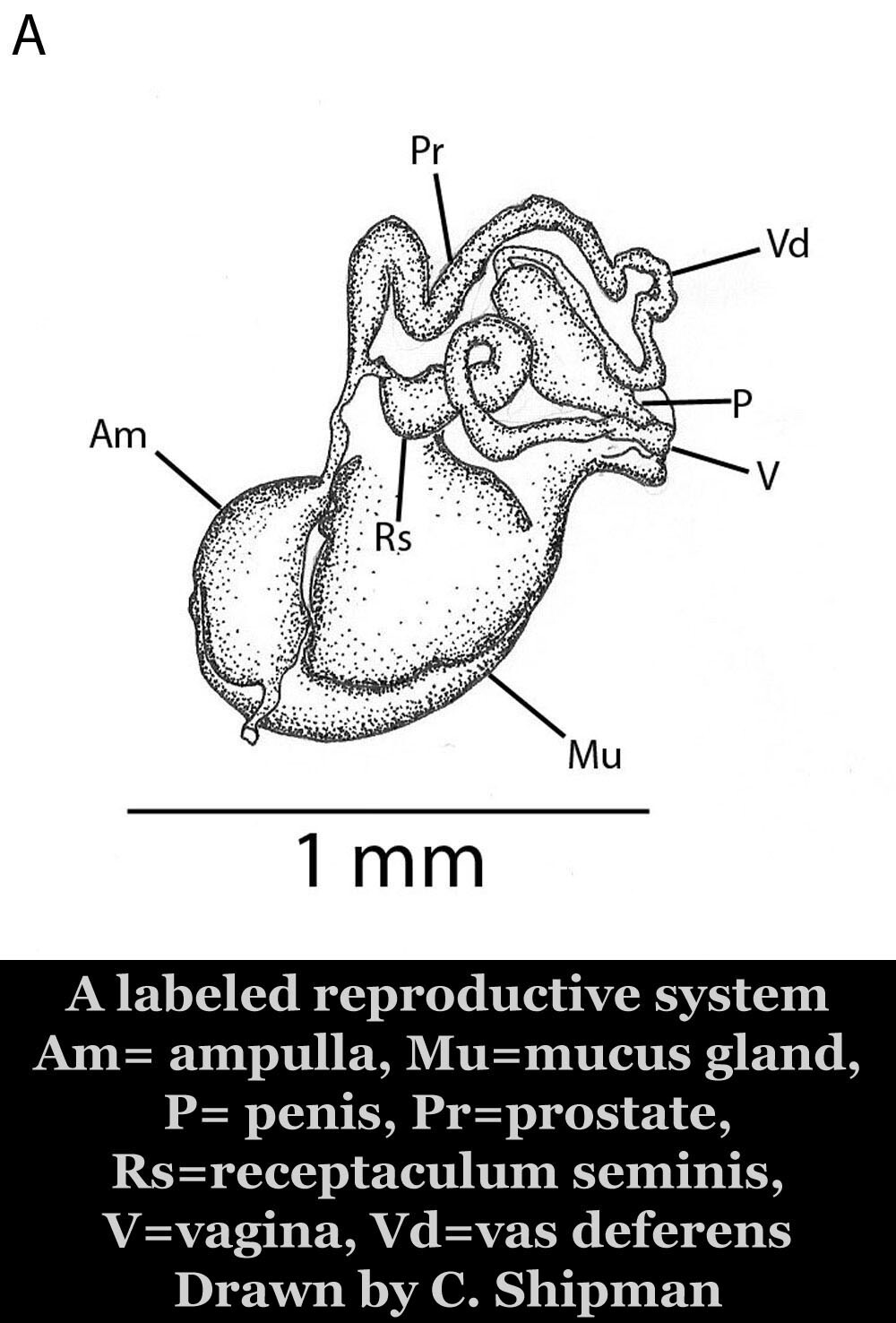

- Nudibranchs are hermaphrodites (having both male and female sex organs), but they still require a mate in order to reproduce as they cannot self fertilize

Above nudibranch reproductive system by Carissa Shipman, found here

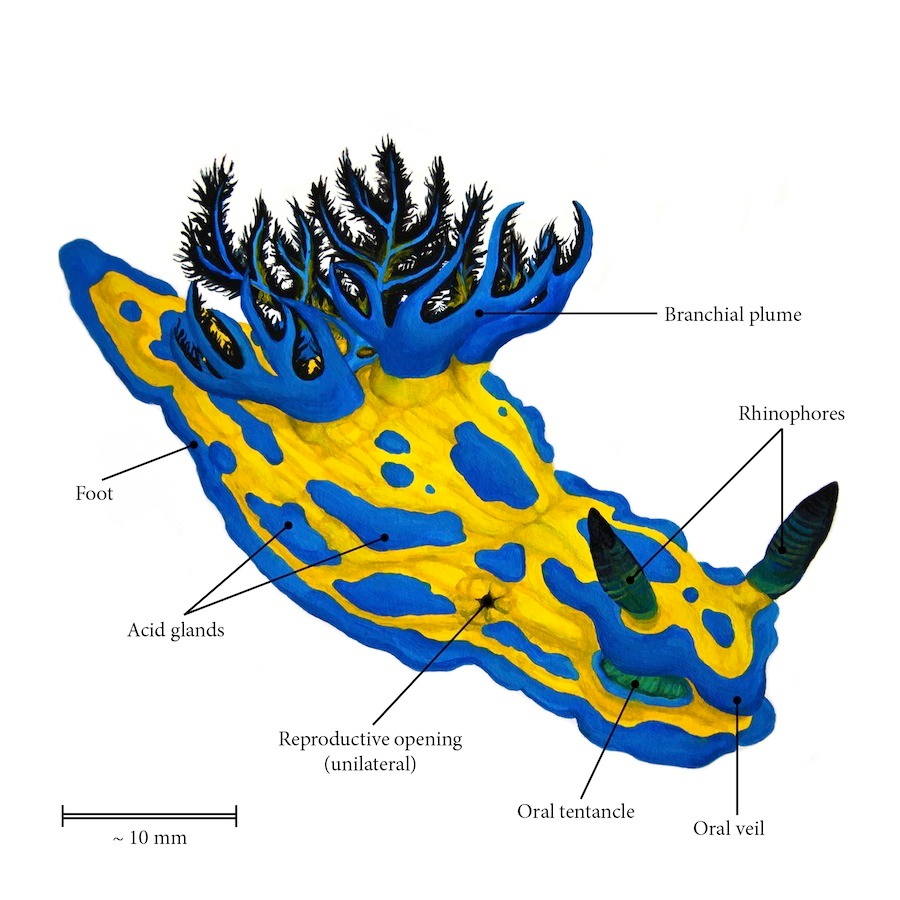

- The reproductive organs are usually next to each other inside the nudibranchs body, and the exterior reproductive opening being on its right lateral side

Above, 'External anatomy of a Tambja verconis nudibranch (by wadeangeliart) found here

- Being simultaneous hermaphrodites increases their opportunities to find a mate, as both partners will transfer sperm, and lay eggs, via reciprocal reproduction.....although there are some exceptions as we will discover!

Above photo Bennett's nudibranchs Mating' by John Turnbull

- Nudibranchs will follow the scent trail left by potential partner. When they catch up with them they start courtship which involves the gentle touching of each other

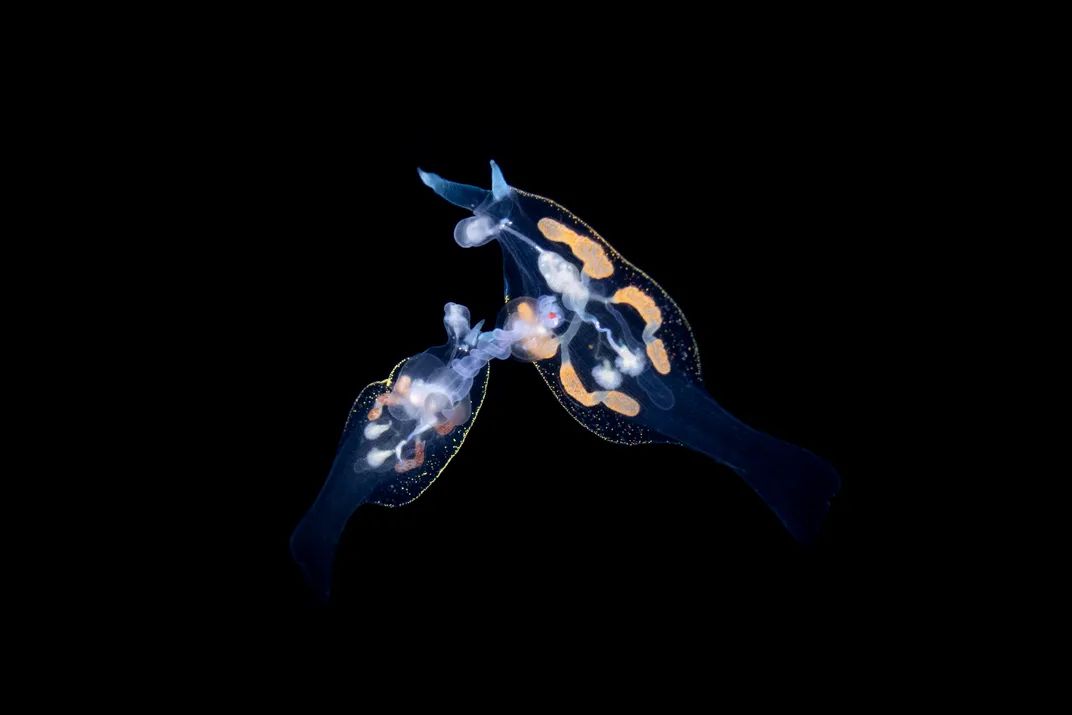

Above photo by ilan Lubitz

- Depending on the species, the nudibranchs will then orientate their bodies so that their reproductive openings are facing, allowing their swollen gonopores to connect

Above photo of Nembrotha chamberlaini mating, by Jim Greenfield

Above photo of Nembrotha purpureolineata, by Brian Mayes

- Nudibranchs will take every opportunity they can to mate when finding a partner. One quirk of their anatomical development whilst maturing into adults is that the male reproductive organs will grow, and be functional before their female organs. This is called protandry....

Above photo of Hypselodoris bullocki mating, by Coppertane....a possible protandry mating, due to size difference

- They can still take the opportunity to mate though as a 'male'..... It has been suggested that any sperm passed to the 'male' partner, can be stored within their bodies until their female organs have matured. It will then use the stored sperm to fertilize its eggs!

Above photo of pelagic nudibranchs mating by Rajiv Bhambri

- Mating duration depends on species, and can vary from brief encounters to several hours!

Above photo by Tony Wu

- There are 3 basic mating positions depending on species- right side to right side..... (see photo below)

Above, Nembrotha chamberlaini, by Andrew Wu

- .....Head to head.....(see photo below)......

Above, Lobiger viridis, from here

- ......And head to tail, which is either a reciprocal, or a unilateral process depending upon flexibility of the species, or even partner aggression......(see photo below)...

Above, Mariaglaja inornata, from here. The genitals are separate in this species- the penis is in the head, and the vagina in the tail

[Above] The gastropterid sea slug Sagaminopteron ornatum will sometimes form a circle of two to achieve reciprocal mating, or at other times as illustrated here, act unilaterally as a male by approaching from behind to copulate with another acting as a female. source

- Hypodermic Insemination is the preferred method used by some species. The penis has a sharp point which is used to stab the partner in order to deliver a packet of sperm. This can be done either as a mutual act, or happening unilaterally with one nudibranch taking advantage to inseminate another....This can occur amongst some of the sacoglassans

Above photo of Costasiella usagi, by eunice khoo....not as cute as I originally thought....

- Goniobranchus reticulatus is an unusual nudibranch as after it has mated the external part of its penis detaches! And within 24 hours it grows back.....!

Scientists think this mating strategy has evolved so the sperm of rival nudibranchs stored in the vagina of their mate will not accidentally get passed on to future mates source

Above photo of Goniobranchus reticulatus by Bernard Picton...with or without penis...(Schrodinger's penis?)

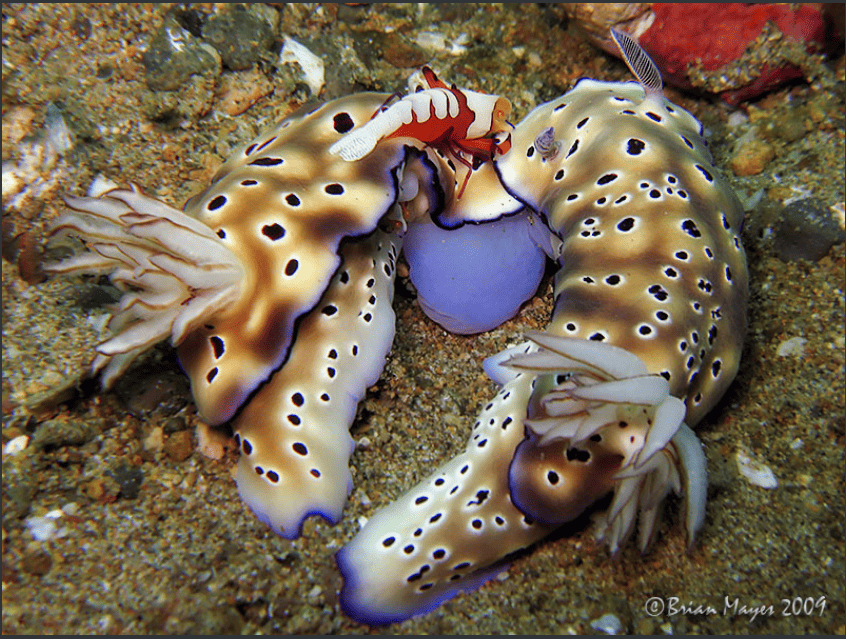

...And finally a shrimp jockey on a pair of mating nudis....

Above photo by Ludovic

Information from-

and the fantastic Nudibranch Domain

As always, I'm not an expert...any errors let me know in the comments, and I'll edit my post!

Main photo..........Spanish Dancer Nudibranch. Photograph by David Doubilet

There are more than 3,000 known nudibranch species, and scientists estimate there are another 3,000 yet to be discovered. So-called Spanish dancers, like this one off the coast of New South Wales, Australia, boast some distinctions over other nudibranchs: First, they can be enormous, reaching a foot and a half (46 centimeters) long. Most nudibranchs are finger-size. Second, it can swim, a skill most of its cousins lack.

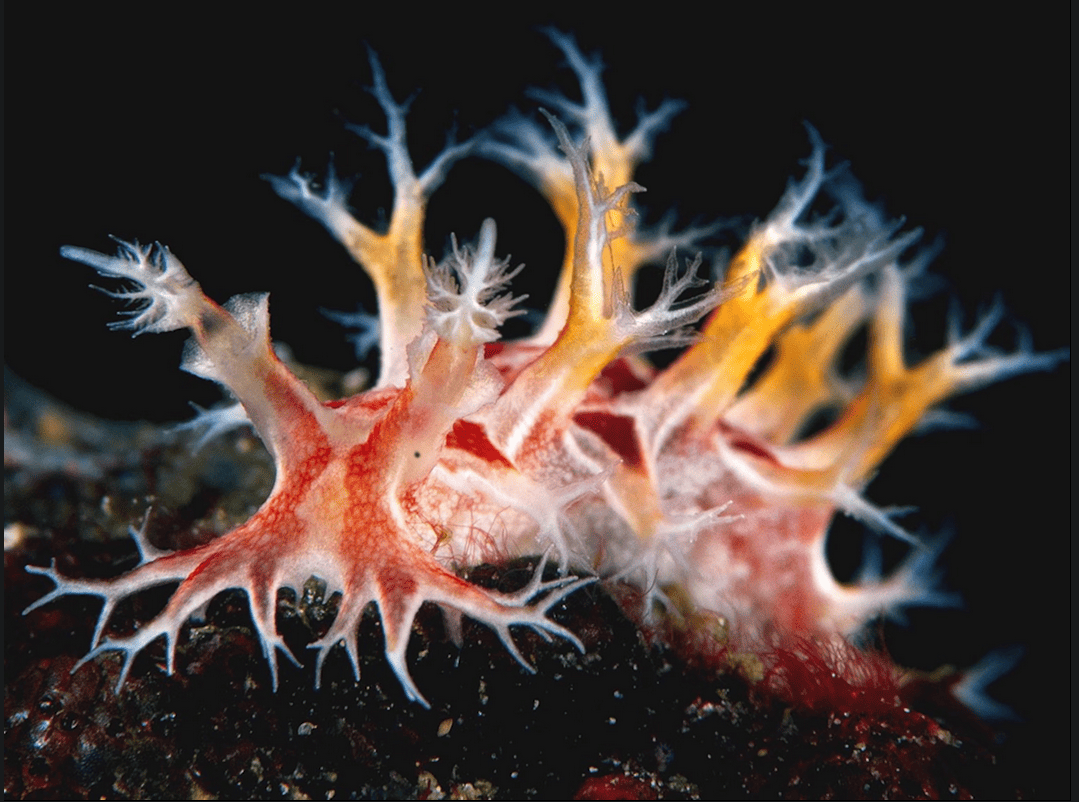

Above, Tritonia Nudibranch. Photograph by Jeffrey de Guzman

Members of the mollusk family, nudibranchs abandoned their shells millions of years ago. Their scientific name, Nudibranchia, means "naked gills," and describes the feathery gills and horns that most, like this Tritonia species, wear on their backs.

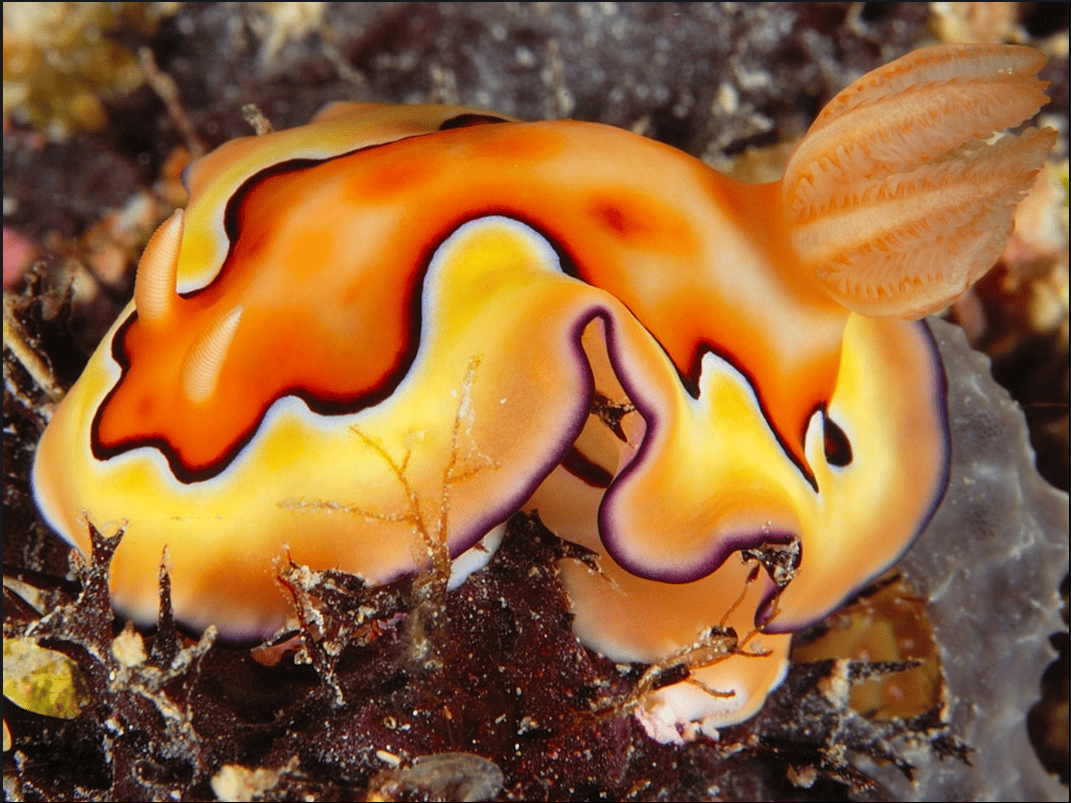

Above, Nudibranch, Philippines. Photograph by Libor Spacek

Nudibranchs, nicknamed "nudis," are best known for the impossible array of colors and designs they sport. They derive coloring, as well as toxicity, from the food they eat. Their wild hues tell potential predators, "You'd best look elsewhere for a meal."

Above, Nudibranch, Palau. Photograph by Ernie Collier

Though partial to tropical climes, nudibranchs thrive throughout the oceans, in warm water and cold, from sandy shallows and reefs to the murky seabed a mile down. Chromodoris nudibranchs, like this one photographed near Palau, are generally a warm-water species.

Above, Egg-Laying Nudibranch. Photograph by Jeffrey de Guzman

Nudibranchs are hermaphroditic, carrying both male and female reproductive organs. Mating pairs fertilize one another and lay up to two million eggs in coils, ribbons, or tangled clumps, as this purple-painted Hypselodoris is doing.

Above, Green-and-Orange Nudibranch. Photograph by Jeffrey de Guzman

Nudibranchs are blind to their own beauty, their tiny eyes discerning little more than light and dark. Instead the animals smell, taste, and feel their world using head-mounted sensory appendages called rhinophores and oral tentacles.

All text and photos from National Geographic

Title photo Emperor shrimp on glossodoris nudibranch, by Ludovic

Above photo by Eric Cheng

-The Emperor Shrimp (Periclimenes imperator) is a species of shrimp with a wide distribution across the Indo-Pacific

Above, Nudibranch (Dermatobranchus ornatus), with Emperor Shrimp by Brian Mayes

-It lives commensally on a number of hosts (this is a long term symbiosis where one species gains benefits, while the other doesn't benefit, but is otherwise unharmed)

Above photo by EcoDivers1

-It will hitchhike on slow moving invertebrates including sea cucumbers, starfish (rare), molluscs...and also nudibranchs!

Above, Emperor shrimp on Nembrotha nudibranch by Roberta Cipressi

-The shrimp is only 19mm, and from it's vantage point it gains access to a stream of nutrients while perched on it's host

Photo by Jessie Weng

-The shrimps vibrant colours advertise the fact that it is unpalatable and help it camouflage on its host

Above, 'Ceratosoma tenue & Emperor Shrimp' by Allen Lee

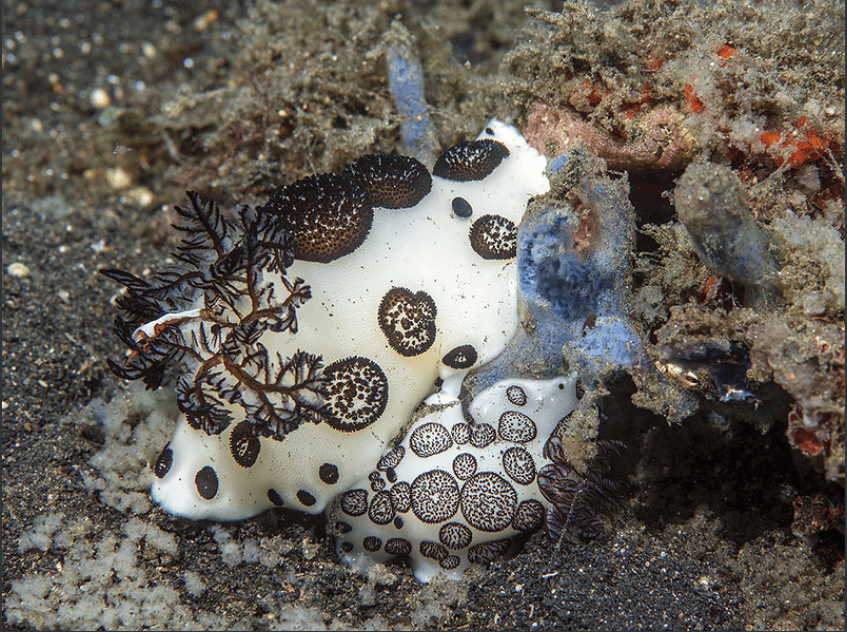

Spot the shrimp.....Above, '(Jorunna funebris), actually two of them copulating. And an Emperor Shrimp...is attached!' photo by Ülar Tikk

-They also help by removing parasites and dead tissue from their host

Above, '(Periclimenes imperator) on a Glossodoris cincta Nudibranch' by Scott Rettig

Above, Tambja morosa with Periclimenes imperator by Benjamin Naden

-They live approx 2-3 years, and will often change hosts. Having a host is essential for the shrimps survival

Above photo by Brian Mayes 'I was surprised to see the shrimp change hosts and leave his small companion behind

-The shrimps are protandrous hermaphrodites. They are born with male reproductive organs and can change their sex to become female as they age and mature

Above photo by Georgette Douwma

-Finding a partner for reproduction can be complex as their dependence on their hosts can impact mating opportunities

Above, '(Periclimenes imperator) takes a ride on a Bumpy Mexichromis (Mexichromis multituberculata)' by David Guillemet

-After finding a suitable mate the female shrimp releases her eggs into the oceans current....

Above, 'Emperor shrimp on ceratosoma nudibranch' by KIYOSHI OKADA

-When the eggs hatch the small larvae will go through several life stages and molts, until eventually finding a companion to ride on....

Above photo by Brian Mayes

....reminds me of being sat on the sofa with my dog.....

Above photo by REINHARD DIRSCHERL

All info from wikipedia and also here and here

Above, 'Zenopontonia rex with Nembrotha milleri' by élanarchist

Above, '(Periclimenes imperator) with a Ceratosoma Tenue nudibranch as its commensal host' by Jun V Lao

I'm not an expert, if there are any mistakes let me know in the comments and I'll edit my post!

Title photo sp. 7 by Ludovic

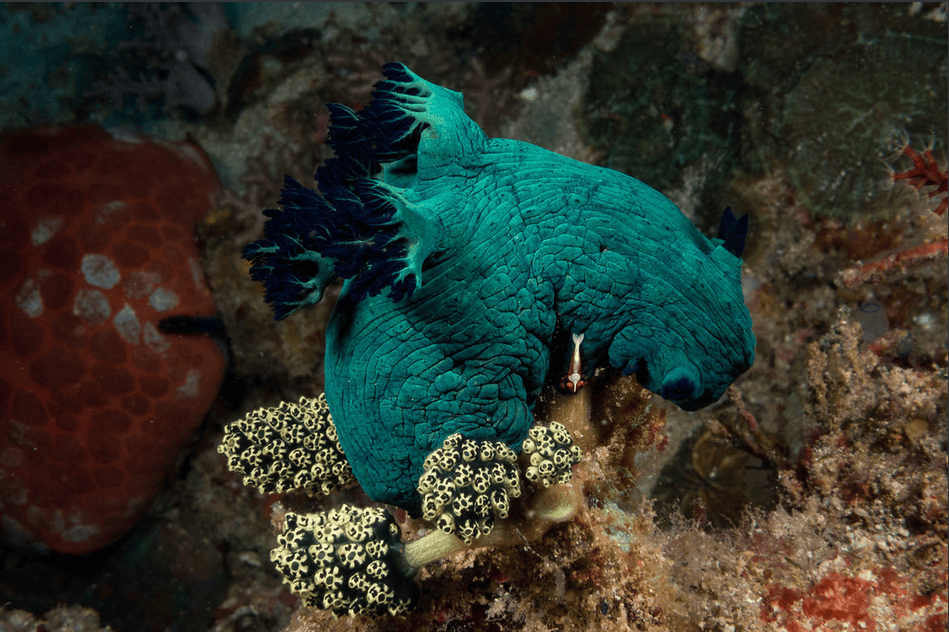

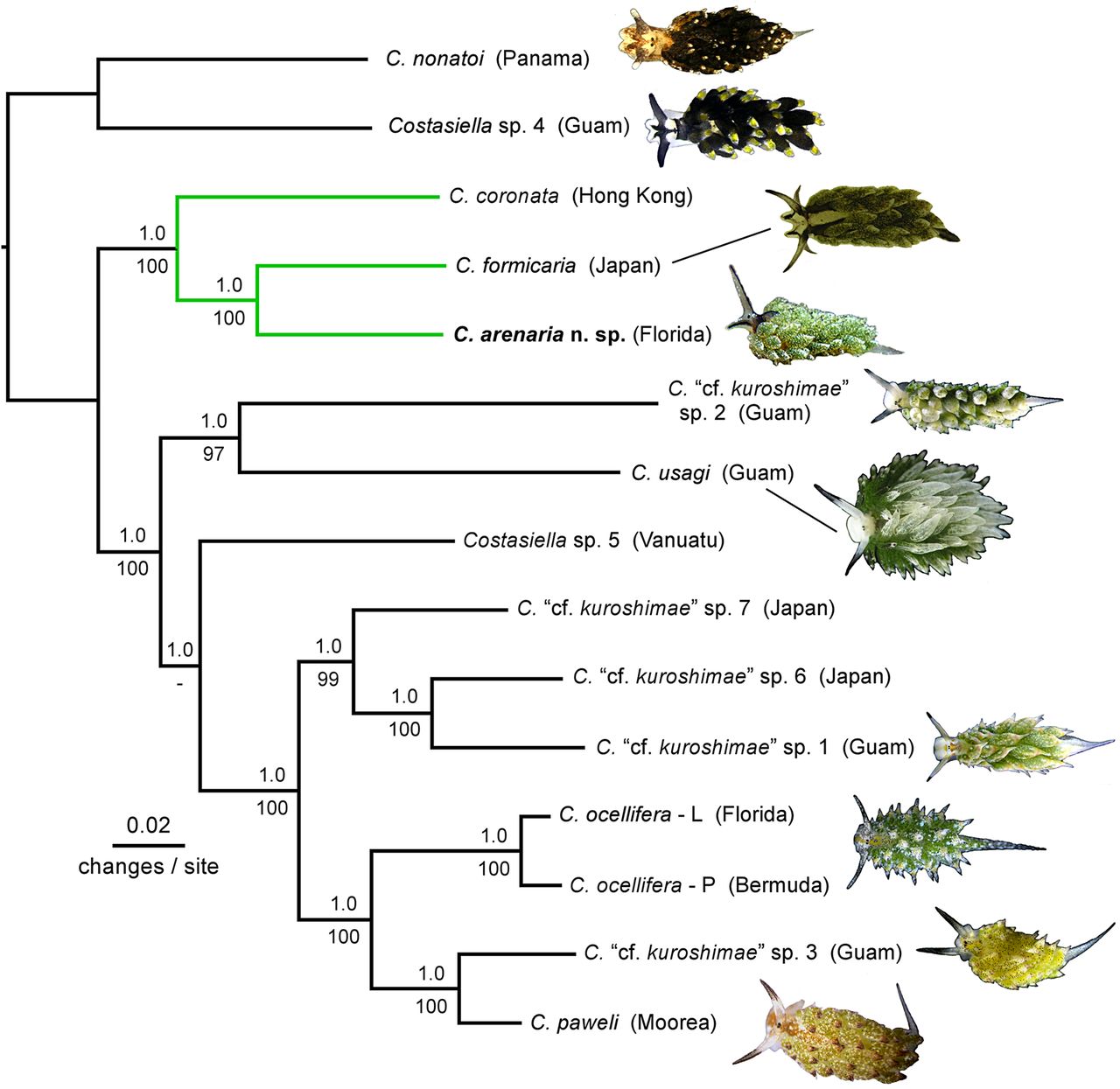

Costasiella is a genus of sacoglossan sea slugs

Sacoglossons are 'solar powered sea slugs' aka 'sap sucking sea slugs' which live by ingesting the cellular content of algae. Some will just digest this fluid, others will store the living chloroplasts in their own tissues, which continue to photosynthesize benefiting the sea slug!

Above photo C. kuroshimae by Michaels Bubbles

There are currently 17 different species in the genus, and they are tiny some are only 2mm! The largest can be up to 13mm!

Above photo sp. 2 by Jean-Marie GRADOT

Costasiella kuroshimae was discovered off the coast of the Japanese Island of Kuroshima, and later also found in the sea off Japan, The Philippines and Indonesia. They have 2 dark coloured eyes, and 2 rhinophores (club shaped structures) that look like sheep ears, these have given them the name of 'leaf sheep'

Above, C. kuroshimae by Anilao~Critters

From the limited information that I could find, C. kuroshimae itself has 7 different types (numbered as sp 1-7) and within each sp there are subtle variations

Above, C. kuroshimae by Todd Aki

Above photo sp. 5 by Anilao~Critters

Above, C. kuroshimae by Vania Kam

Above photo of C. kuroshimae with spiral shaped egg mass, by Kelly McCaffrey

Above 'family tree' of Costasiella, with the different types of C. kuroshimae sp 1-7 source

Other species of Costasiella include C. Usagi....

Above, photo by Allen Lee

Above, photo by Allen Lee

Others within the genus...

Above, photo by Ludovic

Above, photo by Patrick Ess

And finally, some more photos of the Leaf Sheep (C. kuroshimae)....

Above, Costasiella sp. #1 photo by Jenna Szerlag

.......weeeeeeeeeeeeeee!!

Above, Costasiella sp. #1 photo by unknown

Information via wikipedia- Costasiella and C. kuroshimae, also from here and here

Apologies folks, if this post is a bit patchy and garbled, there really isn't a lot of information about these nudibranchs...but I thought the photos were really nice!