What's in a Name?

Did you know that you could get DENIED for what you’d like to name your kid?

Posted November 15, 2011

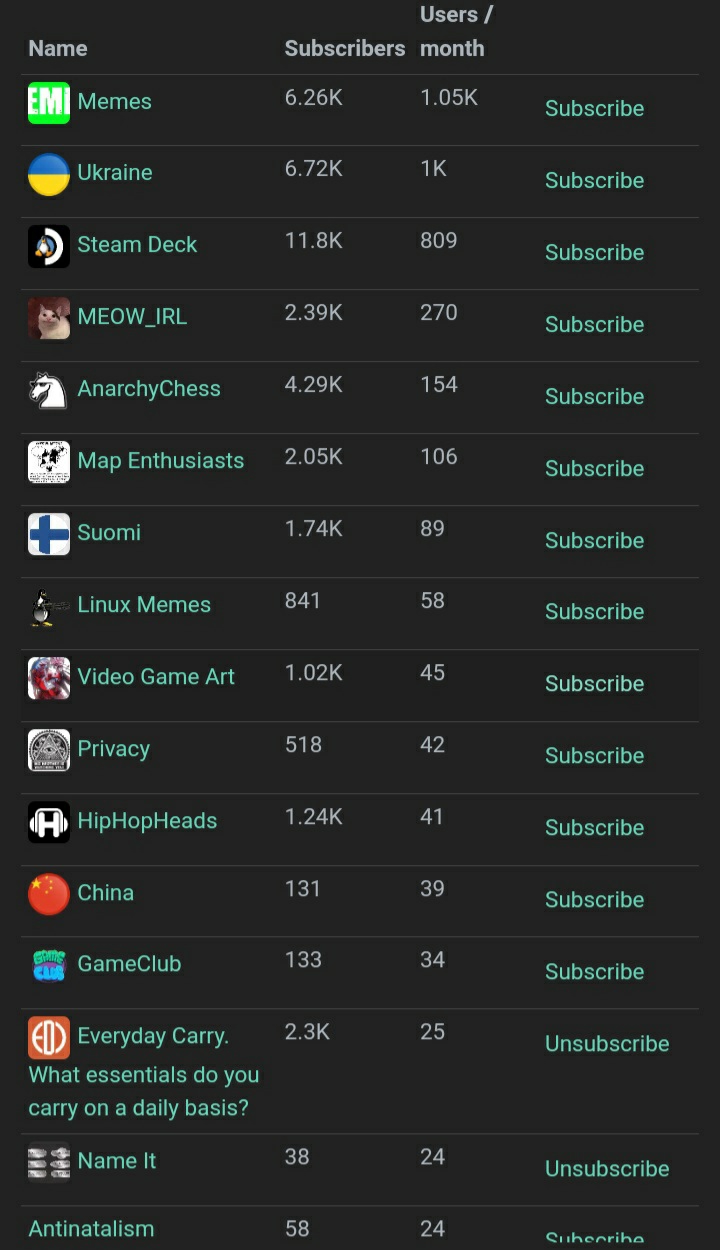

The government of the relatively progressive country of New Zealand recently took a surprising step: controlling what officials considered deviant baby names by banning the use of appellations they have decided are problematic. Kiwis are no longer allowed to call their offspring by names that too closely resemble titles, such as Bishop, Baron, General, Judge, King, Mr., and Knight. Certain letters were also rejected, such as C, D, I, and T. Punctuation marks such as asterisks, commas, periods, and more were forbidden. They turned down three different sets of parents who wanted to name their child Lucifer. Perhaps New Zealanders became sensitive after catching international attention for allowing a couple to name their twins Benson and Hedges in 2008, or for permitting a couple of boys to be called Violence and Number 16 Bus Shelter.

It often is the case that governments react to specific actions that have drawn notoriety by outlawing them. Such reactive labeling has created a host of "odd laws" all around the world, including bans on getting a fish drunk in Ohio or catching them with your bare hands in Kansas, parachuting by unmarried women on Sunday in Florida, driving a vehicle blindfolded in Alabama, eating a lamb after having sex with it in Islamic countries, spitting into the wind in Nebraska, or threatening (let alone killing) a butterfly in California. And France has prohibited naming a pig Napoleon, which gets us back to the idea of deviance in names.

New Zealand is joined in its anti-naming laws by Sweden, oddly enough, another progressive society, which put the kibosh on Superman, Metallica, Elvis, and Brfxxccxxmnpcccclllmmnprxvclmnckssqlbb11116 (pronounced Albin) [what would the artist sometimes known as Prince say about that?], while approving Lego and Google. The Dominican Republic, has begun turning down names that are either confusing or gave no indication of gender, such as Qeurida Pina (Dear Pineapple) and Tonton Ruiz (Dummy Ruiz). Is this, perhaps, a new way that governments are asserting their power to curtail child abuse? Or, have they gone too far in limiting how people name their children, overstepping their boundaries into personal areas?

What is this trend all about? In America, people have a lot of names that might be considered deviant in these other countries. Unusual names are rampant throughout sport, with Stylez G. White, Macho

Harris, Peanut Joseph, Knowshon Moreno, and Selvish Capers having graced the field of football. Baseball has seen Razor Shines, Rusty Kuntz, and Creepy Crespi, along with Sterling Hitchcock, Champ Summers, and Van Lingle Mungo. A few of these odd names even seem like they belong together in pairs, such as Travis LaBoy and Coco LaBoy, Steven Friday and Jeff Saturday, and Antwaun Molden and Anquan Boldin.

Some names, illustrating the principle of "nominative determinism," carry parents' hopes and dreams for their children and may inspire them to follow specific pathways in life, such as Rutgers anthropologist Lionel Tiger, veterinarian and animal behaviorist Michael Fox, Manila archbishop Cardinal Sin, San Francisco dentist Les Plack, and New York attorney, Sue Yoo. Others seem to carry colloquial orientation, such as Symazme Fosho, whose parents, when asked about their child's name, simply pointed to its emphatic nature, as in, "That's her name, Fosho!" Popular among Symazme's cohort is the name Nevaeh, which is Heaven, spelled backwards.

Beckham's child Brooklyn, Ashlee Simpson's Bronx Mowgli, Gwynneth Paltrow's Apple, Jermaine Jackson's Jermajesty, Nicholas Cage's Moxie CrimeFighter, and Frank Zappa's offspring, Dweezil, Moon Unit, Ahmet, and Diva. Are these nominatively determinists? What happened to Sonny and Cher's daughter, Chastity, who turned into a son named Chaz?

Gender-ambiguous or unisex names, also known as" epicene names," have become much more common

(such as Pat, Ryan, Alex, Chris, Sam, with the most currently popular being Rory), despite being outlawed in Germany and other places. Denmark takes an even greater "Big Brother" stance, with a list of 7,000 approved names from which parents have to pick, and anything outside that list requires approval by both the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs and the Ministry of Family and Consumer Affairs.

But what about gender-opposite names, where rather than being unclear, it suggests that the person is of the other gender? We had lunch with a friend, who brought along a buddy of his, a guy named Stacy. During the meal they got into an argument when our friend suggested that Stacy's mother must have hated him to give him that name. Stacy angrily defended his name, claiming it was masculine. In chatting with the waitress as she brought our bill, however, it came out that his middle name was the same as hers: Kimberly. That was too much; he ended up picking up the check after hearing our other friend howl again about how his mother must have hated him.

Name arguments are common. One young man we know named Whitney used to fight with his sister about who their parents liked better, with each claiming the other. In the end, he always won by bringing up his name. He reflected:

Throughout my entire life I have dealt with people's awkward reactions when they know they are meeting someone named Whitney and then realize only when I introduce myself that I am a man. This situation presents itself at work all the time - at an introductory meeting where someone is expecting to meet Whitney, only to see me walking up to them and offering my hand. Their faces are often confused. It also presents itself on the phone, for example when I call and a secretary for the person I am trying to reach needs to take a message. When I tell them who is calling, there is always the need for me to confirm that they heard me say my name right.